My Definition of a First-Class Pull Request

Over the years, I have worked on a few projects where I was the sole developer. Being a sole developer has its challenges since not everyone reviewing your pull requests (or merge requests for the Gitlab folks) has an understanding of the repository like I do. Because of this, I like to give a bit more context to every pull request I create, so reviewers know what to expect when reviewing code.

In this post, I am primarily focusing on pull requests regarding front end development and working on SaaS software, but this format could work for others too. My typical pull request is broken into four main sections: context, testing, checklist items, and then any related GitHub issues or JIRA tickets that will be closed as a result of the merge.

I like small, concise code changes as much as the next developer, but it’s not always possible. Features may span hundreds of lines and have corresponding tests. Having worked with both backend and frontend code, the frontend, more often than not, contains substantially more modifications at a time.

Context

Having context around a pull request is the most important part, aside from the code itself, of course. The dictionary defines context as:

the circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood

With that in mind, we want anyone reading the pull request to have an understanding of what the pull request is about before looking at the code. Yes, your code may be declarative and easy to read with or without comments, but it may not be coherent to the reviewer.

When opening a pull request, ask yourself these questions:

- What is the purpose of this pull request? Is this a bug fix? New feature? Documentation update? Refactor?

- How do these changes solve a particular problem?

- Is there any context outside this pull request that should be surfaced?

These questions can help both you and the reviewer set expectations around what has been changed.

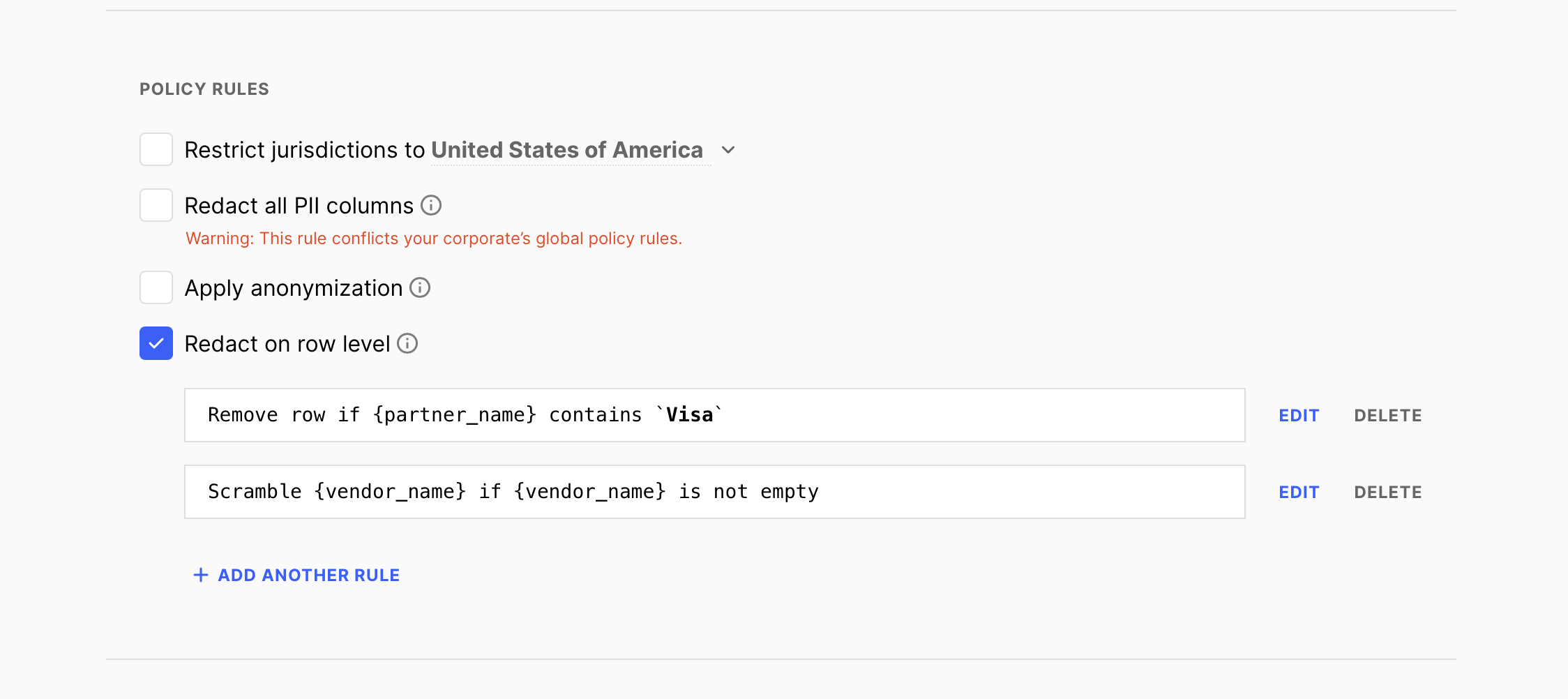

Imagery

Imagery is one category that I think doesn’t get enough attention. If an image is worth a thousand words, why not include one? Instead of putting together a pull request where you changed the button colour to red and describing it as so, why not add an image of the red button? You will likely save yourself time, and the reviewer will now have visual aid.

After implementing a new feature that performs a series of steps, it can be helpful to include a short GIF of it in action. Use any screen recording tools available to your operating system. On macOS, I like to use CleanShot to record an area of my screen. CleanShot is paid software, but there are other free alternatives like QuickTime or open-source like Kap.

Testing

You can refer to this section as defining the steps needed to verify the changeset works as expected. Manually testing may not be required all the time, but it’s a good way to catch errors that you didn’t encounter. When something should be verified by the reviewer, define the individual steps they should take.

Before writing down the steps, include any details around things needed to be present before a successful test can take place. This may involve having additional users seeded in the database, tools required and configured a certain way, or performing an action beforehand.

If a preview environment isn’t available to test on before the changes are merged, consider having a link to the contributing documentation for setting up the local development environment.

I like to use an unordered or ordered list to keep track of the steps necessary to confirm a feature is working. Here is an arbitrary example of what this might look like:

### Testing

⚠️**NOTE:** To verify this functionality you will need **at least two users**

within the database ⚠️

1. Navigate to the home screen

2. Click the **Add/edit users** button

3. Verify a modal appeared and lists X users

4. Click the **(+ add user)** button next to user one

5. Verify the **(+ add user)** button has turned to an **(x remove user)** and

the user has been added

6. Click the **(x remove user)** button

7. Verify the user has been removed

I conventionally follow a pattern of performing an action and then verifying it worked. You can jot down these steps with the same mentality as you would approach end-to-end tests.

Try to keep the steps small and concise so the reviewer can follow along without much effort. It’s possible for them to reach out to you with any questions regarding step X versus describing a step in the middle of a paragraph.

Checklist

Are there items that need to be verified and can’t be automated for each pull request? Include a checklist of criteria that must be true before it can be merged.

Many of these action items are not so much for the reviewer, but for you, the author. These items might include:

- I have added tests to prove my fix is effective or that my feature works

- I have added the necessary documentation (if appropriate)

- I have tested this feature in:

- Google Chrome

- Safari

- Firefox

- Internet Explorer

- Edge

- I have performed a self-review of my code

- I have followed the CONTRIBUTING guidelines

Related Issues and Pull Requests

When the code you’ve worked on relates to a ticket, an issue, a separate pull request or anything whatsoever, include a link to it. This gives the reviewer additional context around why this feature or bug fix was introduced.

Pro-tip: GitHub can automatically close issues by referencing the issue using a simple keyword.

Linking related items helps provide an audit trail for individual pieces of work. It helps anyone look back in months or years from now to see why a particular fix or feature made it into the codebase.

The Pull Request Template

Pull request templates allow all contributors to follow a similar standard. Both GitHub and GitLab give you the option to include one within your repository.

On GitHub, you can place a file named PULL_REQUEST_TEMPLATEin the root

directory of the repository. If you want to keep these files out of the root,

you can place it within a .github folder with the file suffix,

PULL_REQUEST_TEMPLATE.md.

Here is an example you can use to get started:

### Context

- What is the purpose of this pull request? Is this a bug fix? New feature?

Documentation update? Refactor?

- How do these changes solve a particular problem?

- Is there any context outside of this pull request that should be surfaced?

#### Imagery

If you're changing the UX behaviour, include a screenshot or GIF of your

changes.

### Testing

As an end-user, how can I manually verify this code is working as expected? List

out all steps required

### Checklist

Before submitting your pull request, please review the following checklist.

**Put an `x` in the boxes that apply.**

- [ ] I have added tests to prove my fix is effective or that my feature works

- [ ] I have added the necessary documentation (if appropriate)

- I have tested this feature in:

- [ ] Google Chrome

- [ ] Safari

- [ ] Firefox

- [ ] Internet Explorer

- [ ] Edge

- [ ] I have performed a self-review of my code

- [ ] I have followed the [CONTRIBUTING](/CONTRIBUTING.md) guidelines

### Related issues or pull requests

closes N/A

Modify this template to fit your needs or check awesome-github-templates for more examples.

—

I hope this article gave you some ideas of your own on how you can help improve the quality of you and your teammates’ pull requests. Everyone can benefit from the additional context, imagery and testing steps on every pull request. Besides, what’s a couple of minutes to look like a pull request superstar?